1.

The pink blossoms that exist for only a burst in spring were indeed bursting. Amongst the blossoms, a woman, armed with a computer that is also a camera but is known as a phone, was raising her arms to eye level. She caught my attention because the action of raising her arms—and by extension, her phone—indicated to me that she was looking at something of interest. She was standing amongst the bursting pink but it was not the blossoms she and her phone appeared to be enraptured by. I could not see her eyes as her back was to me and her screen was too far away to make out. I tried to infer, based on the angle, what exactly she and her phone were looking at but I could not. The mystery puzzled me and so I filed it away. It was only much later, long after the blossoms were no longer bursting, that I realized she had perhaps been taking a photograph of herself amongst the pink. I’d mistakenly followed the gaze of the phone’s first eye, the one that sits on the opposite side from the screen, when in fact the phone was likely using its second eye, not looking ahead, but behind. The flowers were simply a background, a casual witness to a common relationship: two eyes looking through one eye as that one eye looks back.

Not quite a reflection. Something else.

2.

I’d become inexplicably determined at the end of my first year of university to find a job that allowed me to walk a short distance to work. Given the location of my parents’ house (where I was living at the time) and how short I believed a short distance to be, I had only one option: the zoo. After the formalities of the application process, I was hired as a full-time ride operator, one of the few jobs I was qualified for. This meant that, in addition to pressing the start button on the merry-go-round and assigning appropriately sized life jackets to prospective paddle-boaters, I spent many hours a week driving children—and some accompanying adults—on a five-minute loop around the zoo on a gas-powered train.

The train ride, much like the zoo itself, was an experience. It offered a unique perspective of the zoo and included a (debatably) informative narration. The experience was the product and, in this case, that product was intended first and foremost for children. As a result, parents would often decide to forego the ride, choosing instead to catch a photograph of their children’s faces as the train passed over the bridge (one of the best opportunities for train pictures). As part of the experience, we ride operators would often end up in the photographs parents were taking. In between rides, we would wonder aloud to each other how many family albums we’d anonymously ended up in.

Last year, while working as a delivery driver for a local bookshop, I had a similar thought. On a seemingly innocent front porch, I bent down to place a package of books at the front door. As I looked up and prepared to knock, I came face to face—so to speak—with a Ring. The Ring is a doorbell and security camera that, in the age of online shopping, has become a popular deterrent to porch theft. Like the front porch I found myself on, the Ring is seemingly innocent looking. It presents itself as a simple doorbell. Behind that doorbell, though, is a tiny camera that can connect to your telephone or computer, acting as a digital peephole on the world. To function as a peephole, though, a user must be alert, awake and attentive to their phone and by extension, their doorbell. This is useful if you want to see who’s at the door when the doorbell rings but is a useless tool for catching thieves and vandals. That is, of course, because the doorbell itself is only part of the product. Ring also offers a subscription-based service that allows users to record the footage that their doorbells document for later viewing. Most of this footage is stored by Ring on servers.

3.

The rise of the Internet has led to a steady increase in online shopping and a corresponding increase in parcel delivery. Perhaps no single company can claim more responsibility for the online shopping/delivery boom than Amazon. In 2020, Amazon was responsible for just over 50% of the online retail market in the United States. The company was similarly responsible for delivering more of those packages than FedEx, UPS, and USPS combined, a service that is free for Amazon Prime subscribers (as of 2021 there are approximately 200 million Amazon Prime members globally).

The increase in parcel delivery has unsurprisingly led to an increase in parcel theft, a crime more commonly referred to as porch piracy. A 2021 survey found that a quarter of Canadians have been the victims of porch piracy and a third are afraid of having their parcels stolen. Video surveillance systems have become a popular deterrent to such a crime (a 2019 survey found that 36% of U.S. American homes now have video doorbells) though they are rarely successful in deterring or catching porch thieves.

4.

In the depths of the winter pandemic lockdown, I started playing a video game called Aragami in which you play as a shadowy ninja called (you guessed it) Aragami. Your goal, while moving through the game, is to complete each level without being detected by the opposing army. In order to achieve this goal, you acquire a series of skills as you play. One of these skills allows you to see for a moment what direction each enemy soldier is looking, functionally allowing you to understand which areas of the game are being surveilled and which aren’t. When the power is activated, a series of red cones appear on the screen. Each cone represents a line of sight. For a few weeks, after I’d finished playing Aragami, I continued to see these red cones out in the world. A woman was taking a photograph on the street. Three houses in a row had video doorbells. Security cameras looked down on the parking lot. Red eyes everywhere.

5.

The English word audience can lead us down many parallel paths. One such path takes us to a group, often referred to as spectators. It is undoubtedly a casual settling of language paired with ever-evolving mediums that has allowed an audience to become synonymous with a group of spectators. Follow them back, though, and the two words split at the senses. Spectators, etymologically speaking, are watchers, observers. The word audience, on the other hand, is about listening and being heard.

6.

In our kitchen one evening, Jordan and I were speaking about air purifiers. Arguably not an odd conversation to be having these days. At that point, though, it was just a conversation, a passing thought made verbal. In the days that followed, it seemed that the Internet had the same thought. Air purifiers began appearing in the ads that separate paragraphs on websites, in the blocks that separate posts on social media. It could have been a coincidence. As I said, it’s not an unusual item to be contemplating. Algorithms could be to blame. We had the conversation in our kitchen, two phones sitting idly on the counter, one laptop open and awake, red cones all spiralling out.

7.

Argus Panoptes was a giant with many eyes, a story with many sides. He was a hero for defeating a mighty bull that ravaged Arcadia and for slaying the Satyrs that stole Arcadian cattle. But it was one hundred and two eyes that would seal his fate; his one hundred plus a wandering pair.

In one of his many trysts, the mighty Zeus seduced Io, priestess of Hera. To conceal his affair from Hera, the last of his seven wives, Zeus transformed Io into a beautiful white heifer. Hera was too smart for this. She saw Zeus’s hand and asked for the cow as a gift. Once Io was in her possession, Hera tasked Argus and his hundred eyes with standing sentry over her, preventing Zeus from reaching her again. Argus tied Io to an olive tree and stood watch. You see, Argus had one hundred eyes and they slept in pairs of two, ninety-eight always watching. Undeterred, Zeus tasked his son Hermes, the speedster with winged feet, to steal Io back. It was not his speed that accomplished the task, though, as Argus was never not looking. Instead, Hermes disguised himself as a friend, a fellow herdsman. When he encountered Argus, Hermes enchanted him with pretty tales and on his pipe, he played him pretty songs and softly, before Hermes took his head, each of Argus’s hundred eyes slowly closed.

8.

In 2016, Mark Zuckerberg posted a photograph to celebrate the growth of Instagram, which Facebook had acquired in 2012. Upon seeing the photograph, a Twitter user named Chris Olson noted three things:

Camera covered with tape

Mic jack covered with tape

Email client is Thunderbird

9.

In 2017, Amazon acquired Blink, a video doorbell service. The following year, it acquired Ring.

10.

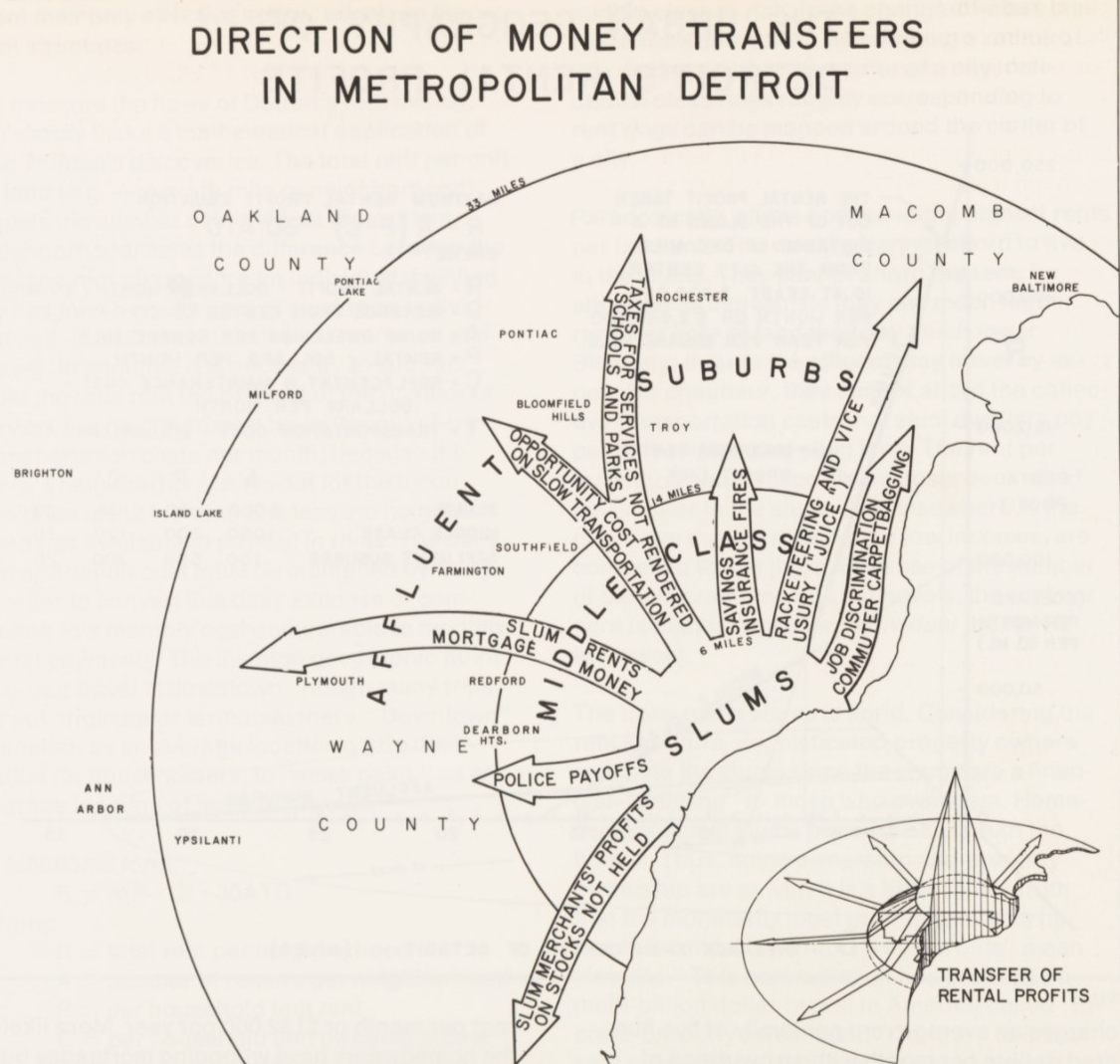

After Amazon acquired Ring, the company began partnering with local police forces in the United States. The partnership allows officers to request the footage from Ring cameras within a certain radius of criminal activity. The requests come from Ring via email along with a message that thanks each user for “making your neighborhood a safer place.” Users can decline or ignore the requests.

In 2019, Gizmodo reported on various alternative methods that police forces have used to acquire information about and from Ring users.

11.

Jon Woodward and Mary Fairhurst were neighbours until watchful eyes drove Mary out. The two lived side by side in Oxford until Jon installed a series of Ring cameras around his property, two of which recorded Mary’s yard and garden. Mary objected to being recorded in her own yard and when the two failed to come to a resolution, the courts became involved. An Oxford County Court ruled that the audio and video recordings of Mary and her yard were her personal data. “The ruling stated that the devices’ ability to capture conversations at ranges of between 40ft and 68ft (12m-20m) away was excessive.” If the goal is indeed crime prevention, the Judge said, then that goal “could surely be achieved by something less.”

12.

It doesn’t take long, when browsing Ring’s website, to stumble across the phrase “Smart security here, there, everywhere.” Security is the product Ring is trying to sell. The core of Ring’s security system seems to depend on the belief that watching eyes and listening ears will keep people and property safe, putting privacy and private property in tension. Personal security, as an industry, is an attempt to make oneself and one’s property free from danger or threat. At the root of security, you find the word secure which points not to freedom but to restriction. This contradiction—bondage that makes one free—hints at the trade that underlies the idea.

The name for the Ring camera is simultaneously playing on the sound a doorbell makes and on the idea of an impenetrable ring of security that the product claims to provide. A ring is also a line curved back on itself and as such, it is a tool for division: inside from outside, victim from vandal, owner from thief. Ring, now a pioneer in Smart Home technology, sells more than just doorbell cameras. They offer a whole range of hardware capable of recording what goes on inside and outside a home. Not just a ring but a web.

A page on Ring’s website reads, “Cover every corner. Inside and out.” The accompanying image shows a man holding a phone, his index finger touching the screen. You can only see a part of the back of his head and his two hands. It’s enough to see that he’s well-manicured, relatively trim, and not Black (this is true of most of the people on Ring’s website). Beyond his extended finger, on the screen in his hand, are two crystal-clear images of an empty home (presumably his). The header at the top of the phone says “Santa Monica” and the icon below it indicates that the system is disarmed. It struck me as odd, looking at the image, that the man holding the phone—who doesn’t seem to be at home—would not have armed the security system in his seemingly expensive Santa Monica house. After all, security is the product, isn’t it? Or perhaps “Santa Monica,” “disarmed,” and two images of a clean and empty house hint at a different product: the calm we can be lulled into when we believe our property, and by extension our lives, are secure.

Etymologically, security can be traced back to the Latin securus which translates as “free from care.” Care, in the classical sense, is intended to mean a state of anxiousness, concern, or grief. But it’s a slippery phrase, isn’t it.

Free from care.

Eyes without tears.

Red cones spiralling out.

Not quite security. Something else.

Publication: Imagining new systems of exchange