This morning, I was reading the essay you shared last week about champagne in Soviet Russia. I haven’t stopped thinking about it, and how it reframes ideas about luxury and value.

Literal champagne socialists! I love the idea of creating luxury outside of wealth—luxury for the people. That article made me hopeful for what could be possible beyond our current economic system.

It was really great. Also, it’s so interesting how the ability to shift a perspective around an object, or a concept, or a relation can do all this work of undoing the problematics associated with it. Maybe not all the problematics, but perhaps it really is just slight shifts that are needed.

I feel like this is something we’ve been talking about: one thing that art can do really well is reframe and recontextualize. It can open up a shift in perspective or shift how we relate to each other and ideas. It’s different from the content of art—I am thinking about how art functions and operates within a wider public, but I know that this can seem pretty abstract.

Yeah, maybe it seems abstract and vague, only because it is actually relational. It’s hard to put into words how the complexity of relations within an exchange happen. But when you experience something in a new way—a way that’s slightly different than what’s typical—it can get you thinking about the way things are. I don’t think engaging with an alternative form of economic exchange through an artistic work gets the public thinking that now we’re gonna overthrow capitalism! But maybe it gets people thinking: I could have a different relationship with my neighbours now; instead of hiring the neighbour kid to mow my lawn, maybe I’ll offer them something in exchange. And maybe that is the power of art: to provide new contexts and to make suggestions for how things might shift.

Yeah, this makes me think of a book I read again last week: The Uprising: On Poetry and Finance by Franco “Bifo” Berardi. It’s from a decade ago, written at the height of the Occupy Movement and the Arab Spring, but was quite prescient on what has transpired since then. Recently, one of the things I’ve been curious about is thinking through how economics, financialization, and precarity inform the art sector and how they shape the relationships and worldviews you are describing. I feel like conversations about money and economics are rarely happening in the arts, or at least not in nuanced ways, but the structures of finance deeply impact the ways we are in relation to each other. To come back to what you were saying, I think there’s potential in art, especially with the kind of practice you engage in, for new ways of understanding to be opened up through experimenting with being otherwise or shaping different ways of relating. A single artwork cannot bear the weight of trying to solve complex social issues, and I think that is precisely where its potential lies. Since art isn’t burdened by outcomes, there is a freedom to think through ideas differently.

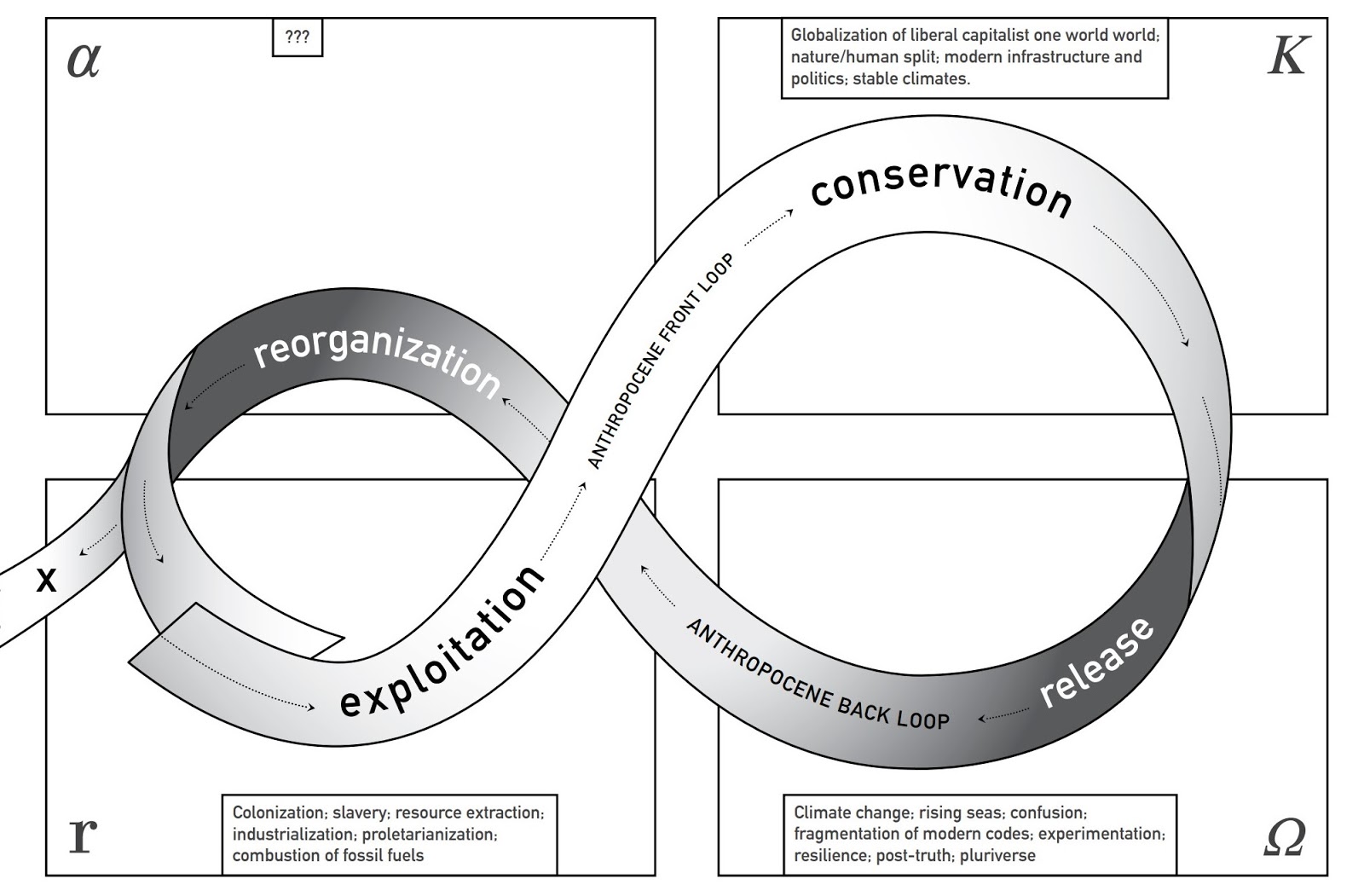

Thinking about these things within an artistic context also allows for the opportunity to try and fail. I’ve been thinking about something that came up in Stephanie Wakefield’s talk about scale, and how failure can sometimes be generative when the stakes aren’t so high (as opposed to potential for the catastrophic when larger scale experiments fail). Maybe the nice thing about artistic practice is that it can experiment with the potentials of larger concepts by working on smaller scales. Even thinking about my seed saving project, I’m constantly shifting the language surrounding it. I’ve changed the title once already. As an example, it began by engaging with language that was much more centered around the idea of “barter,” because when I started the project, I assumed that barter was how these exchanges would go. And when I took the project online I realized, oh no, I think I really mean “trade.” And so, even within the confines of a project, being able to say that something’s not working, and switch things in order to get to a more ideal framework is so important. Maybe there’s something about experimentation that speaks to the abstraction that you mentioned.

And what’s the final title now?

I like how disperse reflects that kind of exchange we’ve been talking about. From our last conversation, I’ve been hooked thinking about El Salvador, currencies, and Bitcoin. It got me thinking about gold and the gold standard, the finitude of resources, and just limits in general. How financialized capitalism is turning everything into an abstraction, where the market has become completely detached from material production. I’m far from an economist, but it is interesting to think of El Salvador’s effort to link their currency with Bitcoin as a move back to something more tangible, like the gold standard. I know that isn’t a perfect analogy, but the number of Bitcoins is finite. Maybe there is something useful in limits that can counter some of the abstraction.

It’s almost like the ultimate agreement in a way, because the limit sets the terms of the agreement. When a resource (or currency, or whatever) is limited from the start, you understand: okay, it can only be utilized in this way, to this degree, and for this long. It’s the potentials of the blockchain behind Bitcoin that I’m most interested in. There are clearly problematics within Bitcoin that have been exacerbated these past couple years, especially as billionaires have started to become more visibly involved with it. But I’m really interested in the notion of it, the potentials: if you insert that sense of abstraction and maybe start considering how money is more than just money—that it is actually something relational—then I think it is super interesting. Considering who sets the terms of that relationality in terms of value is important, but we don’t typically engage with our currency in that way. At its beginning, Bitcoin offered an alternative way of thinking about how we come to engage with currency and ideas around value; it offered an opportunity to exchange with anyone without requiring an intermediary (a bank, or a platform like say, PayPal). It seemed really filled with potential to me: on the one hand, the difficulty with thinking about exchange, and shifting people’s perspectives around how exchange might occur, is bound by how accustomed we are to understanding it in this one standardized and centralized way. Couple this with the fact that the rise of the internet has made a lot of the behind-the-scenes problematics of the market in general more visible. I think that visibility has created an even stronger sense of distrust in the system overall. We’ve watched the market crash in real time a number of times over the past couple of decades, and in some ways, like with that fake Obama tweet, it’s helped people realize just how constructed the whole thing is: how intangible it is, and how it’s controlled by those with money and power.

Speaking of fake tweets, I’m not sure if we want to go here, but it makes me think about how many conspiracy theories have picked up during the pandemic. So wild. There is something about conspiratorial ideas and how they circulate online that I find so fascinating.

Oh yeah, because so much of it is not real. It’s really absurd, actually. I think about conspiracy theories a lot too, and I definitely think it is all related. Conspiracy theories are really compelling stories and how we tell stories is so important. I think there is something related to that in the champagne article too, which is why I was so drawn to it. When we were discussing the article the other day, you said something about how the story in the article is anticipating the scarcity that is going to come. And maybe that’s weirdly what conspiracies do well too, just in a distorted way. Because, yeah, we are fucked, we’re pretty much doomed in so many ways. That is a pretty valid anticipation of the future that we’re heading toward, but conspiracy engages with that thinking in a way that doesn’t offer an alternative or a way out. In contrast, the champagne example offers a shift in perspective that feels more caring.

It’s really interesting, because what you’re saying is within these conspiracy theories is also deeply tied to what fuels white nationalism and all these vicious sentiments. I think that’s why I’ve been so interested in conspiracy theories: how do people come to believe things that are so fantastical and easily disprovable? And at the same time, there are so many things within society (inequality, lack of accountability in government, the shady behaviours of the criminally wealthy) that deserve the level of scrutiny and anger that many conspiracy theories generate.

Yeah, it’s interesting to think about how maybe we had a choice, in a storytelling sense. Maybe there was a fork in the road, 10 or 20 years ago, and this is the direction we chose, and now we’re just on this path of conspiracy. And maybe we didn’t realize it until this year, the degree to which we’re on this totally bizarre path that is not rooted in reality. And yeah, it’s very hard to think about because it’s all very troubling. I think that’s the thing about a lot of conspiracies—which are completely tied white supremacy, absolutely 100%—they are being fueled by a faction of racist fascists who recognize them as an opportunity to gain power. They are also tied to economics. When our systems are doubling down against most people, conspiracies have a stronger chance of taking hold. When you consider technology and automation, and how in the very near future, there just aren’t going to be jobs (as we know them now), it gets really scary to think about just how far these conspiracies and the far right could go.

I’m really interested in thinking about technology in general, but I’m especially interested in AI and the implications of it. One of the predictions—which, you know, isn’t even a prediction, it’s more like a timeline—is that AI is developing at such a rate that, within the next 10 years, you’ll be able to ask an AI to do all of these things that actually employ a lot of people as administrators right now: you just won’t need them. Trainers, even doctors for basic diagnosis. So yeah, as the economy continues in this direction without prioritizing care and solutions for workers, and as these conspiracies continue to take hold, I think more and more people are going to fall for them.

Yeah. Oof, that’s depressing. One of the things that I hope the pandemic has revealed is the centrality of care work for making our system function, and also how deeply undervalued it is. I feel like the labour of care will always resist being reduced to AI, but maybe I am just being naive.

If at any time this undervaluing was gonna change, it seems like it would have been during this past year. It’s really appalling that it hasn’t. I feel like so much of it comes back to economics and markets. If our society was slightly different, if our collective perspectives were driven by even only slightly shifted ideals, that future of care would be really different. What we saw over the past almost 2 years would be really different. I keep wanting to come back to the article on Soviet champagne. Also, because the images within that essay by Yudi Ela are just so mysterious and beautiful.

The images of champagne on tap in all the bars, and the special Soviet version of Chanel #5 perfume are amazing. I had always assumed a culture of Soviet austerity and this really turns it on its head. It’s powerful because it opens the possibility of creating a world that not only meets people’s basic needs, but also allows for pleasure. Everybody gets champagne.

Champagne for everyone! It’s just such a small difference, right? Like, the champagne’s the same, it just comes down to how you collectively think about it. That recent article about Russian champagne trademarks was great, because it helps to point out how much of an illusion it all is. It really comes down to how you think about it, and I think that maps onto how our economic system is built as well. Really, you just need a number of people to think about it differently for it to change.

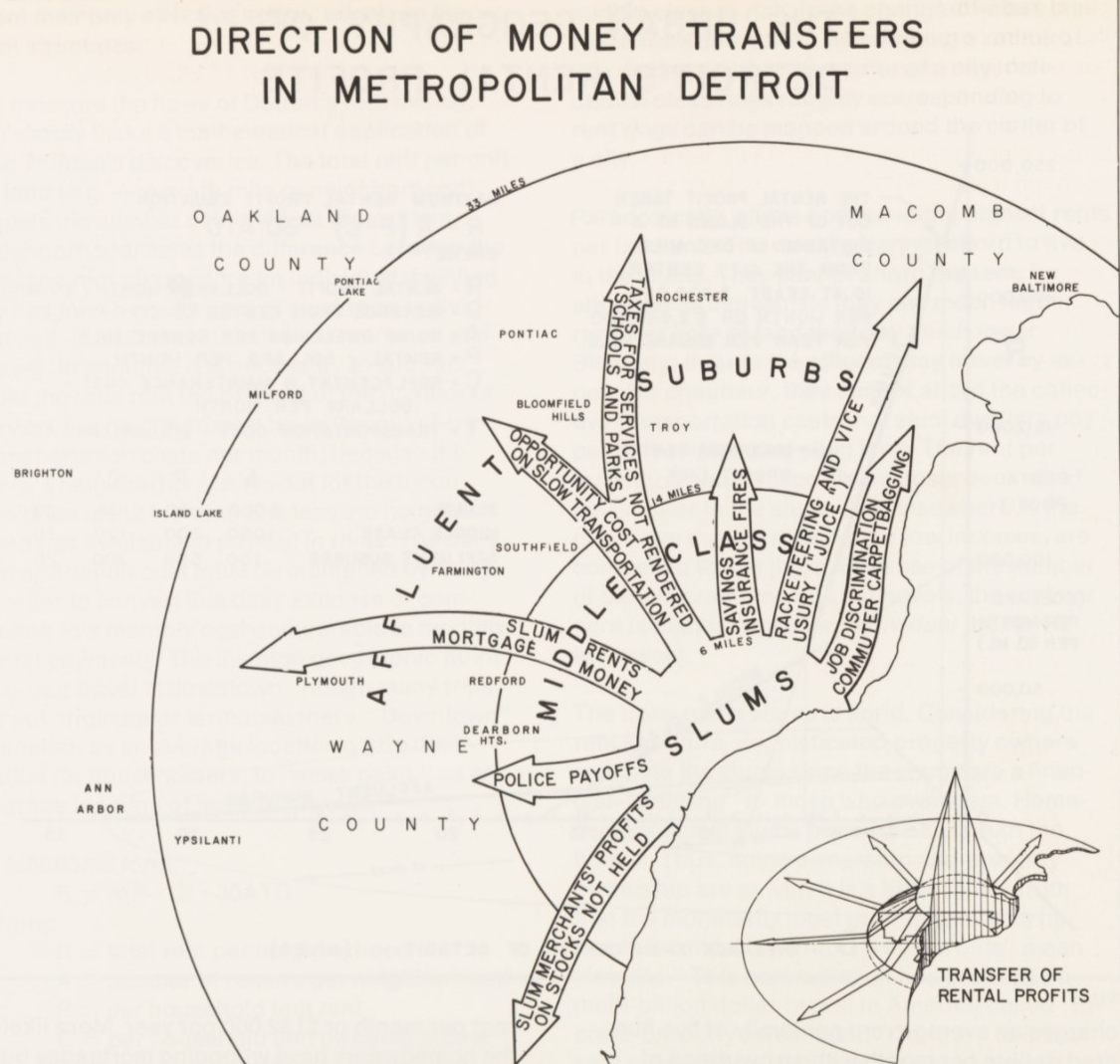

In a very simple sense, social happiness is directly tied to the distribution of wealth. It can be hard to see how wealth is transferred from everyday people to the small group of people at the top, but I am so interested in this movement of money. I think we’ve seen a lot of it during the pandemic, with billionaires dramatically increasing their wealth. Look at Air Canada, which was given huge amounts of bailout money with few strings attached, even when they had laid off almost all of their employees. These wealth transfers can seem so impenetrable and abstract, but really this is how money is moved from public hands to the financial class.

Yeah, you’re totally right. Fundamentally, it’s such a basic concept. I think the idea that social happiness is related to the distribution of wealth is a notion that, fundamentally, most of us understand to be true. We all experience it throughout our lives. It’s so wild how distorted it becomes, how far from common sense. Because we live in societies that don’t care about us, everybody’s scrambling to try to keep it together, and human resources—emotional resources, mental resources—are being constantly shifted in directions that keep us both occupied and distracted. This is why conspiracy works so well. Fundamentally, it’s such a basic thing.

I wonder if there’s also something about transparency there as well. Economies are complicated, unnecessarily so. But while the basics of exchange are actually quite intuitive, the larger economy is not very transparent for most. There’s a lack of access, understanding, and knowledge.

Maybe transparency (or a lack of transparency) is a better way of describing what I mean when I say that these economic systems are abstract. I’m curious about what happens when a system is too complex for an individual to fully understand. It feels like it produces a kind of apathy or inevitability that seems unchangeable. I’ve been reading a book by Charles Eisenstein called Sacred Economics: Money, Gift and Society in the Age of Transition, which proposes that if we shift the way we understand money, we can shift the way we relate to each other and the world. These small shifts in perspective may be hard to achieve on a mass scale, but seem like they hold such potential.

Considering this issue of transparency, I think narratives and stories might be a way to start making things more visible. Because none of it is real. None of it makes any sense, actually. When I first started researching these things, when I was thinking through the financial crisis of 2009 and how stock markets work, I was just blown away by how absurd the whole system was. I started to understand how the stock market functions based on herd mentality and on trigger response. One person starts to get a little freaked out about something, and other people notice, and then they get freaked out about that thing too; it’s contagious. That this is what underlies the framework of the stock market is bonkers to me. How is it that this has such an important place in our economy, whether it makes sense or not? No wonder we’re so collectively prone to conspiracy. Very little of any of this is real, or makes sense.

So much of our economic system functions based on intuition, in a weird way. It reminds me of this article I read about the problem of mathiness and how the field of economics has fallen into this idea that math is the answer to everything.

In that book that I referenced by Bifo, he talks about how economics is considered a science, but it’s not. If science can be defined by the quest for an objective truth that produces consistent results, economics can never hold up to the same level of scrutiny. He argues that economics is actually just a series of social negotiations and—that it is politics that holds all of these things together.

So much of economic theory is fantasy, that’s the other part that is hard to wrap your head around. And, I mean, maybe that also helps us make sense of someone like Elon Musk. Really, it’s all just smoke and mirrors.

It’s pretty wild when you think of it that way. Stock markets and by extension, the economy, are determined by feelings.

I think that’s what I mean. Economic structures, such as inflation or stock market crashes, are very complicated and abstract for most people (including myself) but have deep impacts on our lives. I have started to feel like this so-called complexity is, in part, a tool to keep regular people from engaging with or thinking critically about these structures. Distribution is foundational to care, supporting people, and the planet. Very simply, our current systems tend to consolidate wealth and resources for a small few, removing wealth from people and the public sphere. I’m not sure I know exactly what I am trying to get at, because obviously a lot of the complexity comes from trying to imagine the system’s undoing. I think where art can be useful is that it allows for space to think about the world differently, without necessarily needing to answer these questions in a material sense. To be able to imagine otherwise is invaluable. Does that make sense?

Yeah, I think what artistic intervention can do has something to do with this sense of informed abstraction that exists within practice. It gets me thinking back to the limits around gold. Maybe having something that is limited in terms of engagement and exchange, but also limited in general, allows for visibility. That’s what conspiracies take advantage of: the lack of limits, as well as the lack of visibility. They follow logic to a degree, but then they slip. I think a lot of people get caught within them because they don’t see what is really at the heart of the conspiracy, and then they’re suddenly in too deep. When they might have started out thinking, I’m really pissed off that my local government doesn’t support food banks anymore, or something like that.

Yeah. I was super interested in the conversation we were having around culture and these structures, and how to create the conditions for different kinds of relationships or exchange. Have you been thinking about it more?

I don’t have any answers, but I think one thing that I’ve come to realize is that simply trying different things is maybe my strategy for thinking about it all. Right now, I’m working on this new project that’s quite small, and I realized, actually this is just a slight variation of the same model that my other projects utilize. It’s the slight variations that I’m really enjoying, and I think there’s something important about how these shifts I’m exploring are really small, you know? Especially when thinking about responsibility: responsibility when participating in something, or asking and inviting someone to participate in something.

Yeah, that also seems like it’s part of an iterative process. I’m so curious about that model of working: not being as precious with final outcomes, following intuitions, moving with projects, and continuing to try new things. And yeah, I like your words around it, of wanting to let things go to see how people respond, rather than controlling the final product.

It’s also important to me that it is utilitarian, in a way. My approach is kinda like: you gotta do it, so just do it, and don’t worry about it. In some ways, I still struggle with trying to think about these projects within an artistic framework. I’m very interested in this struggle, actually, and I feel like that is maybe what makes it artistic practice: struggling with being comfortable with it being artistic practice. But I feel like that’s why that lack of preciousness exists for me, so that I can constantly be stuck in that deliberation of how I feel about it as artwork.

Yeah, where’s that tension for you in that? I’m curious about this because sometimes I’m really hopeful about artistic practice, or feel really excited about it being a place to devote energy and time, and sometimes the urgency feels elsewhere. Where does it feel sticky for you?

I think interrogation is part of doing this kind of work. It’s important to ask those questions that challenge: Why are we doing any of this? Especially in an artistic context, why this framing? And something that we keep coming back to is remembering that artistic projects are not going to change these larger systems or societal problems. I think that constantly being in check of this is actually really important. Although sometimes it does feel silly to have to remind people: this project isn’t going to actually change capitalism or whatever (ha!), but hopefully it helps draw attention to it. I think that sometimes in the arts, there is this sense that works that engage with these questions are equivalent to activism: they’re not. I think there can be overlap, for sure, and obviously there is. But I do think it’s important to constantly keep asking those questions and remembering the difference.

Yeah, it’s something that I think about too. It overburdens the work when you ask art to be read as direct action. I heard a really beautiful talk recently on the relationship between ideas and action. I feel like there is often dualistic thinking about the separation between an action and what is presented as ideas, but obviously the two reinforce each other.

Publication: Imagining new systems of exchange