The Part of No Part was an artwork curated by Dan Starling as part of 221A’s Curatorial Residency program where five artists each designed a part of a performance by concentrating on one aspect of it: sound by Julia Feyrer, costumes by Tiziana La Melia, staging by Willie Brisco, choreography by Lief Hall and script by Sam Forsythe. Starting in September 2012, The Part of No Part was presented in an episodic fashion, punctuating the regular programming at 221A over the course of one year and culminating into the grande finale, where each part was performed as part of a whole.

The catalogue includes over 50 colour reproductions of the artists’ work, and the three “scripts” from the performances: Notes from the Overcoat and the Undercoat by Tiziana La Melia, A Letter by Willie Brisco and The Ghost & The Drone by Sam Forsythe. The catalogue also includes contributions from Brian McBay, Benjamin Lobko, Sidsel Meineche Hansen, Dan Adleman and Dan Starling.

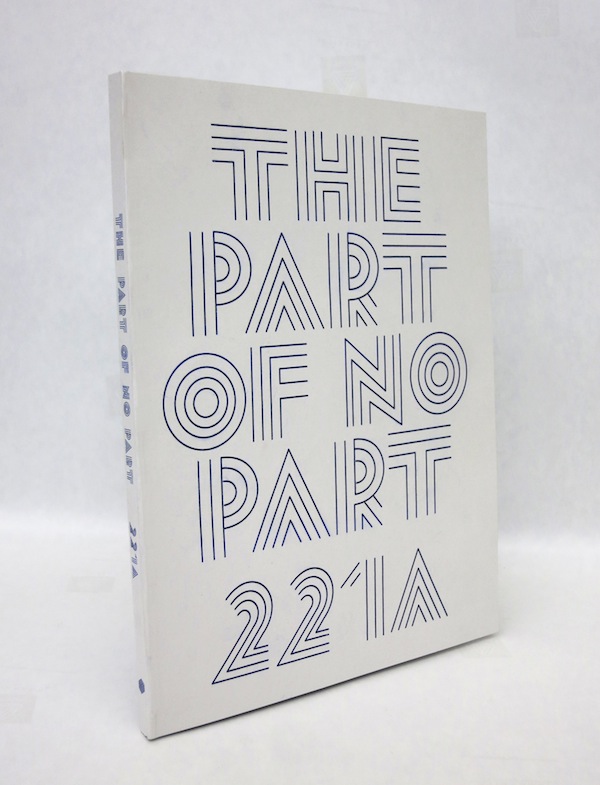

Publication

The Part of No Part Catalogue

ISBN:978-0-9865732-8-6

Edition of 50

146 pp.

8 x 10.5 x .5 in, 500 g

Unsewn Adhesive Bound