Playfulness is a strategy for dealing with power, which is itself never playful.

– Allucquère Rosanne Stone

This inter-view provides a glimpse into an extended and ongoing series of conversations between friends. Here philosophy is an activity and an inquiry that arises out of mutual engagement, attending to and proceeding as the generative potential of friendship. Erdem and I embrace being-with, speaking-with and questioning-with each other, as a loving engagement of conversation that is at once singular and plural.[footnote num=”1″] The dialectical structure of the conventional interview, in which one questions and the other answers, is intentionally set aside. Our commitment to forging a relationship of “significant otherness”[footnote num=”2″] is, for us, a way of thinking about being in the world that opens the possibility for agency, engagement, and intervention in cultural norms that constrict and confine both who we are and how we live, as well as who we might like to be and how we might like to live. Rather than seeking to represent or account for the artist’s work, we choose to “speak nearby,”[footnote num=”3″] hinting towards a third meaning[footnote num=”4″] that is itself fluid, subjective and permanently in process. This text might be read as a metaphor for—or better, in metaphorical relation with—Erdem’s work, opening dossiers of inquiry and coyly gesticulating towards a multiplicity of subjective interpretations and engagements.

As a performative gesture of doing and undoing through reflection and refraction, What a Drag resists full disclosure and fails, rather delightfully, to achieve status as “a superlative mode of signification.”[footnote num=”5″] As Erdem himself suggests, the cheekiness of this work produces a more ambiguous affect, noting that subversive acts and works are often, if not always, both consumed and co-opted by the very mechanisms they seek to critique.

Magnolia Pauker: When I approach your work, I am struck by what I sense as a negotiation of subjectivity, both yours and mine. So, perhaps we can start with this question: How does your subjectivity or subject-position inform the work that you make and how do you conceptualize the relationship between your practice and your contingent existence as a subject in this world?

Erdem Taşdelen: When I talked about my work before I would say that I wanted to talk about my own subjective experiences, but that I didn’t want to be diaristic. Then I started writing the anecdotes in Convictions, the artist book that is being launched with this exhibition, and those are very diaristic. What I’m trying to do is to talk about my experiences in order to see if other people can relate to them, and I’m trying to get better at doing this. If you think about practices like Tracey Emin’s, for instance, there’s a tendency to glorify the figure of the artist, but that is a trap and a danger that I don’t want to fall into.

̶ I was thinking of your work as post-YBA … So it’s interesting that you mention Tracey Emin! I think there’s a connection here and I said post-YBA in order to suggest both an engagement with and a critique of the YBA culture, in particular that kind of glorification of the figure or persona of the artist. Also, you’ve told me that you don’t want to talk about yourself, so I referred to your subject-position or subjectivity rather than self, for this reason.

— Right, because if I speak about a position I take as a subject, that position can be occupied by others too. I don’t have exclusive access to this or that position.

– Perhaps the question that we are addressing is about the line between fiction and non-fiction, as an imposition and an artificiality? This morning I was reading an article by Arundhati Roy and I think that it has to do with what we’re discussing here. I want to read this to you:

Fiction and non-fiction are only different techniques of story telling. For reasons I do not fully understand, fiction dances out of me. Non-fiction is wrenched out by the aching, broken world I wake up to every morning.

The theme of much of what I write, fiction as well as non-fiction, is the relationship between power and powerlessness and the endless, circular conflict they’re engaged in. John Berger, that most wonderful writer, once wrote: ‘Never again will a single story be told as though it’s the only one.’ There can never be a single story. There are only ways of seeing. So when I tell a story, I tell it not as an ideologue who wants to pit one absolutist ideology against another, but as a story-teller who wants to share her way of seeing.[footnote num=”6″]

— That is fantastic! The tension between fiction and non-fiction is a really important point to me in my work. There is no pure fiction or pure non-fiction. All non-fiction incorporates fiction and vice versa. My work comes from a place of non-fiction, but it necessarily turns into fiction in the process of making. By remembering and retelling, I am introducing fiction into it. Thinking about the anecdotes in Convictions, for instance if people ask me if those things really happened, my response would be that it should only matter to me whether they actually happened or not.[footnote num=”7″]Perhaps this is why I’m so interested in Proust’s work.

– “There’s no such thing as fiction or non-fiction; there is only narrative.”[footnote num=”8″]

— If I think of my work as a means to construct a “self” for myself, this has to necessarily include fiction, because the self that one wants to situate oneself as through writing or making is a fictitious self, a self one would like to embody.

– And to claim some sort of purity for non-fiction is to believe that we can actually know ourselves.

— This is all about authority isn’t it? If we give authority to the figure of the author we want them to reveal their souls to us. One of the people whose production I like to think about most is PJ Harvey. I was very obsessed with her music in my teenage years. A lot of the music I was listening to at the time had a claim to being non-fiction, whereas PJ Harvey was one of the only people I knew of who would explicitly say, “I don’t understand why people assume it’s me speaking through my lyrics. My work is fiction.” This comes through in her lyrics; she performs different people. She performs her work very queerly too.

– So perhaps there is a fetishization of the performance or of the representation of the artist in particular, whose persona, it seems, we are inclined to take as non-fictional?

— Yes, if it’s non-fiction it’s as if it’s going to be more authoritative or credible. One of the other difficulties I have in formulating and conceptualizing my practice is that the subjective experiences I reference by taking myself as a case study can be clichés. And I like clichés. I like using them and talking about them. I think there is a tendency in contemporary art to belittle daily clichés, but I care more about what people who aren’t well-versed in art history think. Take the letters I wrote in Dear, for instance. They are entirely made up of clichés. And anyone could write them, we’ve all experienced those clichés.

– Clichés exist for a reason. I noticed that you used the phrase “case study” and you refer to “your case” in your series titled But to return to my own case, … Would you say that there is a certain ambiguity produced by the titling of this series, in how you’re framing your subjective relation as a case? There is the “case study” as an objective instrument of scientific discourse and there is also the psychoanalytic case. Is this reference perhaps a nod to pathology and the pathologization of your case? Why do you use that word?

— I hadn’t thought about the connotation of pathology there, which is interesting. The title of that work comes directly from Proust. It’s the beginning of a sentence in Time Regained where he explains that he thinks of his readers as readers of their own selves, with the help of his “case.”[footnote num=”9″]

– This seems to be precisely what you’re advocating in thinking through your subject position in relation to your work. And you’ve said that one can only ever produce work from one’s own subject position. But in returning to your own case, your own case is actually about your relationship with others. Perhaps it’s not merely a return, or a cloistered return, but also an invitation and an extension?

— The word “case” also signifies that there is an experience that can be thought to apply to different subject positions, and when I apply it to my way of being in the world it’s a “case” of that relatable experience. This is why I have been writing the anecdotes in Convictions, with the hope that others might relate to them.

– I was also thinking about the relationship between anecdote and aphorism, which I sense in a number of your works as a central concern. Your anecdotes are diaristic, yet I don’t feel like the reader is led to a clear conclusion. They’re not transparent.

— Most of my anecdotes end with an expression of how I felt in relation to the experience. It could have happened to other people, but when it happened to me this is how I felt. This acknowledges the specificity of my subject position and my entry into remembering. Things happen to me all the time, but why is it that I remember these moments? It’s a subjective selection.

– Or maybe even objective in the sense that we have little control over what we actually remember, perhaps as a quilting point[footnote num=”10″] between the conscious and the subconscious self?

— Of course, there’s involuntary memory. Proust writes about how we can’t help remembering certain things, and we don’t have control over what will make us remember either.[footnote num=”11″]

– Yes, I think that this is suggested in the way that your aphorisms read.

— I feel slightly uncomfortable with the word aphorism, though. I think that an aphorism comes from a specific figure who is granted privilege for their wisdom. I don’t want to see myself as that figure.

– But there are aphorisms that are not initiated by any specific figure and do not have an author. I think of aphorism more as an opaque suggestion for thought and thinking. Maybe a classical aphorism is about truth or the telling of a story, but at least for me, after Kafka, I understand the aphorism as an enigmatic form—a riddle that queers itself[footnote num=”12″] and frustrates any straight-forward reading. The ambivalence of readability and in particular of the relation between the artist and the artwork seems to me a fundamental concern for you. Would you agree?

— Yes, I do think about how I want to present myself to the world with all of my works. There are a lot of other formal variations these works could have taken, or other concerns I could have addressed, but I’m making specific decisions I feel comfortable with. The work allows me to negotiate how I want to show myself.

– But it’s not really you…

— Exactly. It’s a constructed me; it’s how I would like to construct and position myself. It’s a performance.

– Yes, I think that performance and performativity are key concepts in relation to your work. The performance—or better, the performativity that you enact—is self-conscious, self-critical and also not necessarily always of your “self” or subject-position. The Drag Series, for instance, leads me to think of the performativity of language and its gendered vectors.[footnote num=”13″]

— Yes, and there is a performative humour in much of my work, which is even more pronounced in The Drag Series. Humour is a way of dealing with making work that’s coming specifically from a subjective experience and it opens a point of access for the audience. And there’s self-ridicule involved …

– Yes, I sense that the self-ridicule also extends to or opens towards the conundrum of criticality and art making within the gallery system and capitalism at large. You have discussed this conundrum in relation to the way in which Erdem Taşdelen,[footnote num=”14″] your business card work, could be understood as a critique of the relationship between art and business or art in the capitalist system. You noted that there is always the potential for that kind of critical work to be consumed by, incorporated into and ultimately co-opted by the system that it seeks to critique.

— And I am well aware of the fact that I function within that system, so the last thing I want to be doing is to put on a pretense of critical distance.

– What are your responsibilities or ethical concerns, then, as an artist?

— Maybe in thinking so much about how I perform myself I want to encourage people to think about how they might do that, how they might construct their own subjectivity. I find it to be an important thing to consider, because we are constructed by so many things that influence us in the world, but at the same time there are “technologies of the self,”[footnote num=”15″] as Foucault would call it, where you can willfully make yourself the person you want to be.

– And yet not quite. There isn’t freedom. Judith Butler puts it really well, saying: It’s not that we’re free to choose not to have a gender, but that even while we are constrained inside various apparatuses of power, we have a certain agency to choose how we perform gender—though it is also imperative to note that even, or rather, especially, this choice is always already contingent upon and curtailed by a social relationship.[footnote num=”16″]

— Yes, Butler advocates for subversive little acts. I wrote about this in my thesis where I did a comparison between Slavoj Žižek, Butler and Foucault’s ideas around agency and power. Of course I feel more akin to Butler. Žižek says that we have to overturn the system completely with a revolution[footnote num=”17″], whereas Judith Butler says we can only work within the system and try to disrupt it with subversive acts that will accumulate over time.[footnote num=”18″] We can only work within the system.

– There is no outside. We cannot leave.

— Exactly. Even what seems to be outside of the system is in fact always inside. And for me the making of work is engaging in subversive acts too, even if it’s only a personal subversion. I often think of new work and think to myself, “Can I do something so ridiculous?” And then say, “Yeah. I can do it.”

– You are experimenting with failure and its potential.

— Yes. It took me a while to feel comfortable with experimentation.

– Of course. To step outside of your safety zone is not an easy thing to do. Do you feel you’re doing that with The Drag Series?

— Yes, absolutely—more overtly than with other works. The first instance where I really started to ask myself, “Can I actually do this?” before making a work was with Dear,. When I started writing the letters I didn’t think I was working on an art project, then I realized I was spending a lot of time writing these and thought, “Well, if I’m doing this instead of making work, why isn’t this work?”

– You said that Convictions started in this way as well. So in a way your life is your work, or rather, you are problematizing the distinction between life and art.[footnote num=”19″] We’ve been talking so much about your subject position—we’ve talked about you, your relationship with the work—and I realize that maybe this is the one medium that you consistently take up with each of your works.

— Myself?

– Yes, or your subjectivity, your subject positions and your critical relationship to contemporary culture, both in terms of art and popular culture, if we could even deign to distinguish between the two …

— I think that comes from the fact that I’ve always had to think about my subjectivity. I don’t know if this is the case for everyone, but I suspect it isn’t. I don’t think my mom’s constantly thinking about her subject position and who she is in the world. I’ve had to go through a lot of changes in my life in various places and in different social environments. I’ve always had to situate myself in those environments.

– You’ve also had to do so as a minoritized subject.[footnote num=”20″]

— Exactly, that’s why I’ve had to consider how to situate myself. I expect that some people would find the question of what a self is redundant, since it’s often taken as a given. And fifteen years from now I might be thinking, “I’m so fucking tired of constantly having to situate myself, I am what I am.”

– Thinking about The Drag Series and its relationship to minoritization, I feel like what you’ve produced is the spectacular or hyperbolic image trace of what is still a minoritized subject.

— I think that in this series what I’m more interested in is the majoritization of minoritized subjectivities, or what becomes the dominant expression of a minoritized subjectivity.

– Yes, or the way in which popularization can be a form of spectacle.[footnote num=”21″] It is a question of how minoritized subjectivities become majoritized—co-opted within the majority—which is itself a spectral entity in any case. I am thinking of the way that things become images, the way that we are inclined towards consuming images, or perhaps the concern that you and I share with regards to, or, as Roland Barthes puts it: “I am only wondering about the enormous consumption of such signs by the public.”[footnote num=”22″] Would you say your work might enact an implicit critique in this regard? Still, I’m not trying to box your work into this critical discourse. How do we articulate it?

— I know, it’s difficult to talk about it in terms of a critique of something for me, because it doesn’t initially come from a place of deliberate critique. It feels almost contrived to say, “I am critiquing this.”

– But sometimes theory arrives late to the party.

— It does, but I don’t feel comfortable saying, “These are the things I want to critique with this work.” I mean, let’s try to think about how critique happens. As soon as I try to refer to my work explicitly as a critique it becomes, for me, a conceptual abstraction rather than an opportunity for embodied experience. Perhaps I am saying, “Look, I have a problem here, guys and girls. I’m suggesting what my problem might be. Are you with me?” Critique is also about affect, right?[footnote num=”23″]

– So it’s a question? A series of questions?

— Yes, rather than propositions.

– I really want you to read Bracha Ettinger’s text on the generative potential of art where the subjectivities of artists and audiences are brought together in an affective relation in response to the work itself.[footnote num=”24″] She talks about the way in which the relationship one has with a painting can become diffuse. What you’re saying is that your subjective experiences might, while remaining yours, be shared and that through this gesture, the subjectivity that is registered in your work may encourage others to consider their subject positions and subjective experiences. Ettinger calls this process artworking, after Freud’s notion of dream-work.[footnote num=”25″] So there’s a sort of psychoanalytic opening among various subjects that happens, and her discussion is specifically related to the traumatic traces that are registered in a work of art and somehow apprehended or affected communally.

— I tend to think of affect as something that is experienced more bodily or viscerally. My gut reaction is to say that my work is not really about affect, but maybe that’s a hasty response. Something that’s visceral, I think, is a response to physicality, and the physicality of my work is a consideration that at times eludes me. I’ve had a lot of trouble with this because it’s crippling when I try to find the perfect form that, in fact, doesn’t exist. After such endless deliberations I came to a point where I decided, “If I think about this all the time then I can’t make work’ this is not something that can be resolved.” So now I try to go ahead and make things without worrying about the perfect form.

– And perhaps you’re making works and conversing with ideas that you don’t necessarily always realize you’re going after?

— Yes, and that is part of affect.

– I was thinking, when you described affect as visceral and physical, that laughter proceeds from an affective response as well. The kind of humour that is deployed in your work might also be generative of an affective, even affectionate relation.

— Yes, and humour is not formulaic, where x equals laughter. It’s hard to articulate why good humour is humourous. I’m not talking about comedy—comedy is more overt, whereas humour is affective.

– It strikes me that your description of humour could be thought of in relation to speaking about art. As soon as you try to explain why it’s art or what it means, it’s dead. Humour functions in a similar way.

— In terms of intentionality too.

– It always escapes our intentionality, right? That which strikes you as very humourous isn’t necessarily taken up as such. You are talking, then, about how humour is a critical strategy. You’ve also described your work as “cheeky.” What does that mean for you?

— Well, for one, if I embark on a project with the initial premise of, “Can I really do this?” then there is something cheeky in taking that stance.

– Again, humour seems crucial here. If someone says, “Can I do this? Yes I can,” with a sense of humour, there’s a different kind of “yes” implied, one that doesn’t take the self too seriously—unlike, say, the case of Emin.

— There’s inclusivity through humour, I think. When I look at Emin’s work, I don’t feel included and I certainly don’t smile or laugh. I just wonder why she’s overwhelming me with all this really personal stuff, and it feels like too much information. As an artist, I don’t want to be giving too much information.

– But I also know that you’re not the kind of person who does not want to be confronted with what’s difficult or what’s really personal. So why this response to that work, as compared to someone else’s? Can you think of another work or artist who deals with intensely personal subject matter, yet provokes another response for you?

— Félix González-Torres. Emin’s work feels exploitative in its overtness and its demand for emotional response. Rather than offering something that might elicit a response from the audience through which they can think about their selves, Emin seems to be saying, “Look at me, focus on me, feel this, be crushed by this.” Whereas with González-Torres, although I don’t see any humour in his work, there is something I can relate to more and I don’t think that has anything to do with gender or sexuality either.

– So there’s a necessary opacity in approaching a work. If it clearly articulates what it is, it’s over.

— And as for the humour, I don’t think he makes work that is explicitly personal, but I really appreciate Farhad Moshiri’s work and its cheekiness.

– I think some of Barbara Kruger’s work is humourous. It’s aphoristic too.

— Yes, and that is the kind of humour I appreciate. Elmgreen & Dragset’s Powerless Structures series is brilliantly humourous. One of the installations in this series is a “queer bar” where the bar is enclosed and the seats are on the inside. No one’s actually occupying it and there is no way in or out; one could only sit inside, but one would not be able to go outside.

– It seems to me that each of the artists who we’ve mentioned are interested in commenting upon—even intervening in—normative cultural transmissions and hegemonic power relations. Would you say that you’re playing with and questioning the construction of meaning? Barthes refers to ideological or mythic language and images as a “superlative mode of signification.”[footnote num=”26″] When I read that phrase recently your XOXO flashed into view. We could see this work as an investigation of superlative modes of signification? What might that mean?

— I think about the performative aspect of that kind of signification in XOXO, where the signification seems to be about signification in the first place. Maybe we could call it a meta-signification. In a lot of my work, and this series as well, I think about how the phrases themselves interpellate the viewer and situate them as specific kinds of subjects. Take hey girl hey, for instance. The form doesn’t translate into the content; they’re not the same thing. The content you get from the form is not the content that you see—it’s an affective content.

– So affective content opens the relation between form, content, artist and viewer? You’re artworking! Sandy Stone has said that: “Playfulness is a strategy for dealing with power, which is itself never playful.”[footnote num=”27″] I am thinking of this insight in part because of the way you describe the relation between form and content and also with regard to the titling of the series. In referencing drag you’re referring to queer performance and by extension performativity and gender constructions. So is there a political relation being established in or by this work?

— I think the political relation is being established between me and the viewer, especially in Vancouver more than other places, where by making and showing such work I am inevitably taking a political stance. I imagine a lot of people, even my friends, would come to this exhibition and think, “Who makes work about gender anymore? That is so passé.” And this has so much to do with power and invisibility, not necessarily their power, but the power that we’re all subjected to. The political act occurs in the decision where I say, “Yes, I can do it and I will do it.” I will not be told that this is out.[footnote num=”28″]

– So, gender is out! I’ve just been reading an article about how part of the displacement of the focus on gender might come from an increased focus on queer theory. Does this mean that queer is in.[footnote num=”29″] What does queer mean for you?

— I think you may be right about queer being in in academic circles, where queer theory is branching into various other disciplines and queering them, but I’m not sure that this translates into popular culture. Perhaps “gay” is in, but not queer. If you see an ad for a bank with an alpha gay male couple, I hardly think that’s about being queer. I like to think of queer more as a verb than a noun. Queer is not something that can be attained, it’s a limit to strive towards. And here the word “limit” is used in the mathematical sense, where a close abstract value is assigned to functions which do not have a definite value. One is never queer enough one must always queer oneself. In one of the anecdotes I wrote for my book, somebody asks me if I think I might fall in love with a woman someday, and because I say no I feel I’m not queer enough. And that’s what queer is, constantly becoming different.

– It’s a responsibility.

— Yes, it is an ethical responsibility.

– This is how Avital Ronell, after Jacques Derrida, describes responsibility where the responsible one is the one who has never felt herself to be responsible enough.[footnote num=”30″] Or thinking with Donna Haraway, responsibility is about taking a stand for some ways of being and living and specifically not for others.[footnote num=”31″] It is not an openness in terms of anything goes, but an intentionality towards sheltering otherness or difference; for example, the performance of drag as a celebration of gender non-conformism. Can you tell me what drag means to you?

— For me thinking about drag is acknowledging that all gender behaviour is drag. In titling this work The Drag Series I’m not only talking about the common notion of drag as stage performance, but the idea that gender itself is a drag. So perhaps the work is more about gender than queerness. It’s only queer because I’m queer. I’m not fully sure that we would focus on queerness if this work was produced by a heterosexual woman.

– Another way of thinking about queerness, for me, is that it is that which thwarts easy consumption of an image or understanding, interrupting and undermining the quest for certitude. Queerness is a refusal to submit to the tyranny of norms and normality. Butler has described Kafka’s The Cares of a Family Man as a queer text, persistently queering the possibility of a straight-forward reading, pushing us off in our attempts to make sense of it.

— I would hope that something similar could happen with The Drag Series, where it would become more about an affective response rather than a clearly articulated critique. When I put the pieces together in a gallery space, I want people to come in and be very aware of the work’s overtness and dramatization. I almost want people to say, “Yuck.” I’m hoping that this overtness might induce nausea in people. Maybe that’s where the critique emerges.

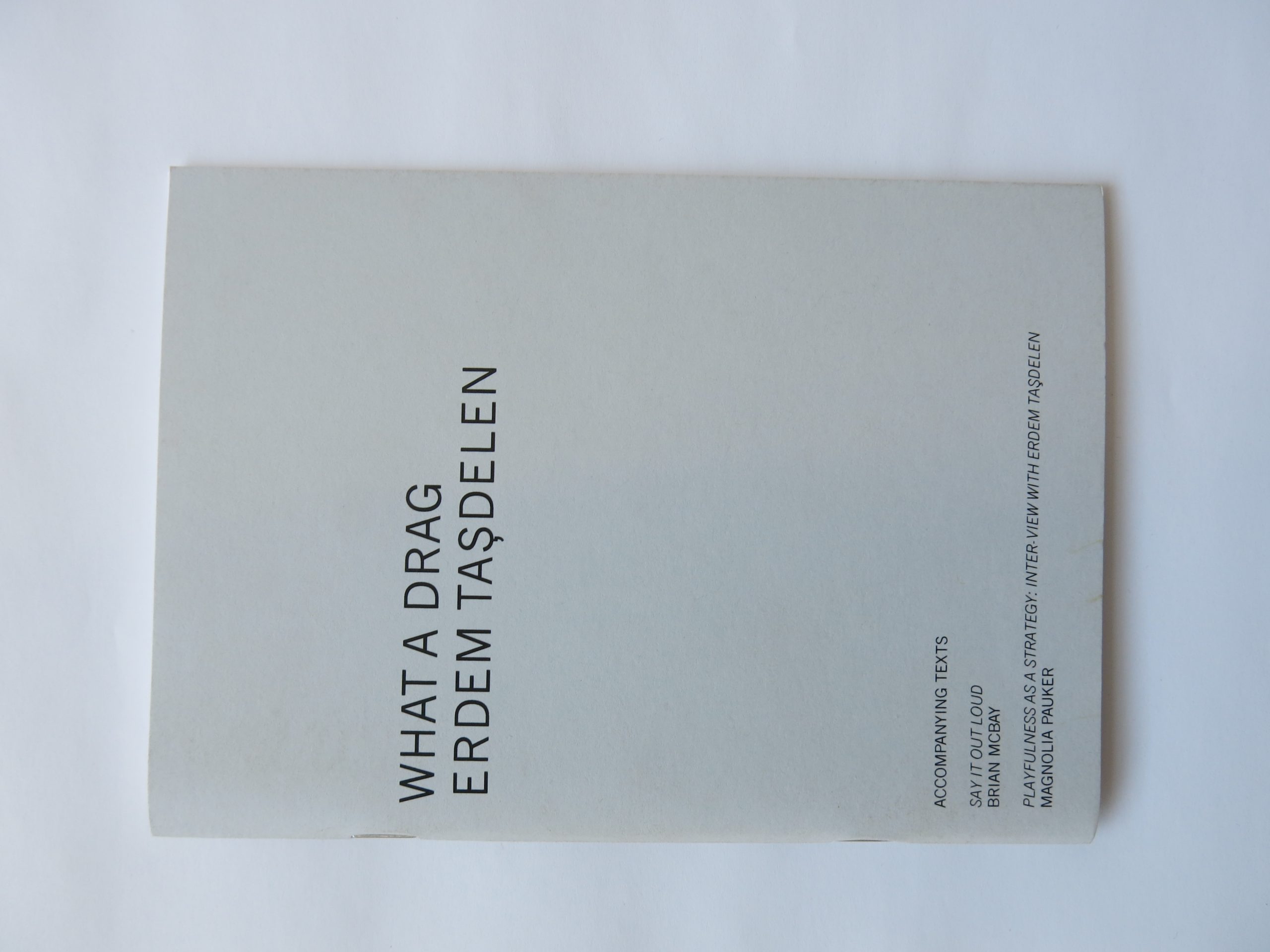

What a Drag: Accompanying Texts

Edition of 200

ISBN:978-0-9865732-4-8

References

- Baghramian, Nairy. 2011. “You go first….” Texte Zur Kunst. 22 (82):50-54.

- Barthes, Roland. 1972. “The Iconography of the Abbé Pierre.” Mythologies. Toronto: HarperCollins.

- Barthes, Roland. 1978. “The Third Meaning: Research Notes on Some Eisenstein Stills.” Image Music Text. New York: Hill and Wang.

- Benjamin, Walter. 2005. “Hashish, Beginning of March 1930.” Walter Benjamin Selected Writings: 1927-1934, Volume II, Part I. Boston: Harvard University Press.

- Butler, Judith. 1997. Excitable Speech: A Politics of the Performative. New York: Routledge.

- Butler, Judith. 1997. The Psychic Life of Power. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

- Butler, Judith. 2011. Lecture. The European Graduate School. Saas Fee, Switzerland. August 8.

- Butler, Judith. 2004. Undoing Gender. New York: Routledge.

- Chen, Nancy. 1992. “‘Speaking Nearby:’ A Conversation with Trinh T. Minh-ha.” Visual Anthropology Review. 8(1): 82-91.

- Debord, Guy. 1995. The Society of the Spectacle. New York: Zone Books.

- Doctorow, E.L. in Geoffrey Galt Harpham. 1985. “E. L. Doctorow and the Technology of Narrative.” PMLA 100(1):81-95.

- Ettinger, Bracha. 2006. The Matrixial Borderspace. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

- The Examined Life. 2008. Written and directed by Astra Taylor. 87 min. Sphinx Productions. DVD.

- Ferguson, Roderick A. 2003. Aberrations in Black: Toward a Queer of Color Critique. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

- Foucault, Michel. 1988. Technologies of the Self: A Seminar with Michel Foucault. Boston: University of Massachusetts Press.

- Freud, Sigmund. “The Dream-Work.” 1997, 1913. The Interpretation of Dreams. Ware, Hertfordshire: Wordsworth Editions Limited, 169-352.

- Haraway, Donna. 2003. The Companion Species Manifesto. Chicago: Prickly Paradigm Press.Haraway, Donna. 1997.

- Modest_Witness@Second_Millenium.FemaleMan©_Meets_OncoMouse™: Feminism and Technoscience. New York: Routledge.

- Kaprow, Allan. 1966. Assemblage, Environments & Happenings. New York: H. N. Abrams.

- Lacan, Jacques. 1997, 1993. The Seminar of Jacques Lacan: Book III: The Psychoses 1955- 1956, edited by Jacques-Alain Miller. New York: W. W. Norton & Company.

- Lee, Pamela M. 2011. “Post-Feminism… Post-Gender?” Texte Zur Kunst. 22 (82):42-49.

- Nancy, Jean-Luc. Being Singular Plural. Stanford, California: Stanford University Press, 2000.

- Proust, Marcel. 1999, 1931. In Search of Lost Time: Volume VI: Time Regained. Translated by Andreas Mayor and Terence Kilmartin. New York: Modern Library Paperback.

- Ronell, Avital. 2002. Stupidity. Chicago: University of Illinois Press.

- Roy, Arundhati. 2002. “Not Again.” Guardian Weekly. September 30:23.

- Stone, Allucquère Rosanne. 2003. Lecture. The European Graduate School. Saas-Fee, Switzerland. June 18.

- Trinh, T. Minh-ha. 1985, 1982. Reassemblage. Camera Obscura. 13-14:104.

- Žižek, Slavoj. 2009. The Ticklish Subject: The Absent Centre of Political Ontology. London: Verso.

Footnotes

Jean-Luc Nancy, Being Singular Plural. Nancy proposes an ontology of “being singular plural,” in which the “with” is “radically thematized as the essential trait of Being” (34). Being is never only being; it is always already being-with. “Co-existence” is existence from the outset, from its “co-origin” (187). The singular necessitates the plural; individuality constitutes multiplicity. “Singularity is indissociable from a plurality” (32). Thus, Being Singular Plural is an event of possibility overturning the dialectical opposition of the One and the Other.

Donna Haraway, The Companion Species Manifesto, 3.

“I do not intend to speak about. Just speak nearby.” Trinh T. Minh-ha, Reassemblage. For Trinh this gesture of speaking nearby is “a speaking that does not objectify, does not point to an object as if it is distant from the speaking subject or absent from the speaking place. A speaking that reflects on itself and can come very close to a subject without, however, seizing or claiming it … Truth never yields itself in anything said or shown… Truth can only be approached indirectly if one does not want to lose it and find oneself hanging on to a dead empty skin.” Trinh, “’Speaking Nearby:’ A Conversation with Trinh T. Minh-ha,” 86.

Roland Barthes, “The Third Meaning: Research Notes on Some Eisenstein Stills,” Image Music Text.

Barthes, “The Iconography of the Abbé Pierre,” Mythologies, 47.

Written September 11, 2002. Arundhati Roy, Not Again.

Thus Albert Camus famously remarked that, “fiction is the lie through which we tell the truth.”

E.L. Doctorow, E. L. Doctorow and the Technology of Narrative, 81.

“But to return to my own case, I thought more modestly of my book and it would be inaccurate even to say that I thought of those who would read it as my readers. For it seemed to me that they would not be my readers but the readers of their own selves, my book being merely a sort of magnifying glass […] it would be my book, but with its help I would furnish them with the means of reading what lay inside themselves.” Marcel Proust, Time Regained(In Search of Lost Time vol. 6), 508.

Jacques Lacan, The Seminar of Jacques Lacan: Book III, The Psychoses 1955-1956.

Marcel Proust, In Search of Lost Time.

Judith Butler, Lecture.

Judith Butler, Excitable Speech: A Politics of the Performative.

Erdem Taşdelen, Erdem Taşdelen, Box set of 48 individual business cards, 2011.

Michel Foucault, Technologies of the Self: A Seminar with Michel Foucault.

Judith Butler, Undoing Gender.

Slavoj Žižek, The Ticklish Subject: The Absent Centre of Political Ontology.

Judith Butler, The Psychic Life of Power.

“The line between art and life should be kept as fluid and perhaps indistinct, as possible.” Allan Kaprow, Assemblage, Environments & Happenings.

Avital Ronell, Stupidity, 27. See also Roderick A. Ferguson, Aberrations in Black: Toward a Queer of Color Critique.

Guy Debord, The Society of the Spectacle.

Barthes, “The Iconography of the Abbé Pierre,” 48.

“From another stage: my first experience of audition colorée. I did not fully appreciate what Egon said to me, because my apprehension of his words was instantly translated into the perception of colored, metallic sequins that coalesced into patterns.” Walter Benjamin, “Hashish, Beginning of March 1930,” 328.

Bracha Ettinger, The Matrixial Borderspace.

Sigmund Freud, “The Dream-Work,” The Interpretation of Dreams.

Barthes, “The Iconography of the Abbé Pierre,” 47.

Allucquère Rosanne Stone, Lecture.

“The gender debate of the nineties was at least still an issue that allowed people who pursued it to claim that they were in tune with the zeitgeist; today, by contrast, serious engagement with feminist concerns seems to have become a drag.” (emphasis added) Nairy Baghramian, “You go first…,” Texte Zur Kunst, 50.

Pamela M. Lee, “Post-Feminism… Post-Gender?,” Texte zur Kunst.

Avital Ronell, The Examined Life.

“The point is to make a difference in the world, to cast our lot for some ways of life and not others. To do that, one must be in that action, be finite and dirty, not transcendent and clean. Knowledge-making technologies, including crafting subject positions and ways of inhabiting such positions, must be made relentlessly visible and open to critical intervention.” Donna Haraway, Modest_Witness@Second_Millenium.FemaleMan©_Meets_OncoMouse™, 36.